Because you seriously can’t have too much of this sort of thing, I am shamelessly stealing Alyssa Rosenberg’s idea of telling Hollywood how to fix itself and produce films about women, for women, starring women.

In her original piece, Rosenberg says that “the number of leading roles for women has actually fallen since 2002, from 16 percent of protagonists in top-grossing films to 12 percent.” TWELVE PERCENT. Yeesh.

Though I totally applaud her concept, I have to admit I am not familiar with a single one of the books she referenced. I read something else by Tamora Pierce one time, but that’s as far as it goes.

So, without further ado, here are my suggestions for stories Hollywood should be telling, and the actresses to help them tell those stories:

Jennifer Lawrence as Murcatto, ‘the Snake of Talins’, Best Served Cold

Joe Abercrombie’s First Law books inhabit a very distinct world which is explored over many volumes. However, Best Served Cold is a standalone novel with a female protagonist I hesitate to describe as tough as nails. She makes nails look like they’re made of blancmange.

As you may gather from the title, it’s a grand revenge drama. Women never get to star in revenge dramas (with the notable exception of Kill Bill). It always bugged me in the Crow that after Eric Draven is murdered, and his girlfriend is raped and murdered – he’s the one who gets to come back for vengeance. Surely she was more wronged? More deserving of revenge and closure? Sigh.

So it’s a revenge drama, it’s also a heist – two things that Hollywood loves – and it’s insanely violent. In the wake of Game of Thrones, grim dark fantasy is big business. Hollywood, you are crazy not to be making this film already!

Sophie Turner and Stephanie Cole as Sophie Hatter in Howl’s Moving Castle

Now, I know Hiyao Miyazaki already did a pretty good job at a film adaptation of Diana Wynne Jones’ much loved Howl’s Moving Castle. But two things: 1) we haven’t seen a live action version, and 2) it was a very loose adaptation. I would love to see a much more faithful version of the story: very English, very traditional.

Turner could do a good job of showing us Sophie Hatter as a mousey, put upon young shop assistant – nurturing a spark that will come to fruition by the end of the story. Cole would be marvellous as the cranky, forthright Sophie after she falls under a spell that ages her 90 years – and allows her to blossom into her true, assertive, magical self.

Saorise Ronan as Tally in Uglies, Pretties, etc

Scott Westerfeld’s Uglies trilogy (later quartet) is perfect for Hollywood right now: dystopian societies on the verge of collapse! Underdog revolutionaries! And at the heart of it all a questioning of all our trivial, shallow, self obsessed values, of our desire to inhabit some perpetual arrested development. All that, plus some kick-ass action and extreme wish fulfilment makeovers (if you like that sort of thing). Ten years since it’s release, it’s only becoming more relevant to our celebrity trivia obsessed culture.

Ronan is a fine actress, and has action credentials (see Hanna). She has the kind of face that can be plain or stunning, depending how she’s presented. And although significantly older than Westerfeld’s protagonist, is able to play young. Make this happen!

Maisie Williams as Cat Royal in The Diamond of Drury Lane, etc

After her attention grabbing performance as the child refugee-turned-killer in Game of Thrones, I’m sure Maisie Williams has offers queuing round the block – probably for action-oriented roles. But I’d like to see her do something a bit different.

After her attention grabbing performance as the child refugee-turned-killer in Game of Thrones, I’m sure Maisie Williams has offers queuing round the block – probably for action-oriented roles. But I’d like to see her do something a bit different.

Julia Golding’s Cat Royal books are joyful, exuberant, perfect entertainment for children and adults alike. Cat is smart, passionate, impetuous, and kind-hearted. She’s more of an evader than a fighter, but she’s undeniably tough. I bet Maisie isn’t getting offered any roles like that, and I think she’d be great at it.

Raffey Cassidy as Melanie in The Girl with all the Gifts

I’ve struggled to come up with a young lead for M R Carey’s terrifying tale of the sympathetic but deadly zombie girl on the run in post-apocalyptic London, but Raffey Cassidy fits the bill. She has a surprising amount of experience for such a young actress – she played the young Kristen Stewart in Snow White and the Huntsman, and is set to co-star as a robot with George Clooney in Tomorrowland. She also has a definite look – you could believe there’s something a bit uncanny about her.

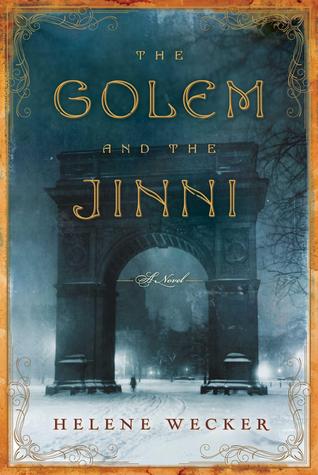

Hayley Atwell as Chava in the Golem and the Djinni

Helene Wecker’s magical, wonder-filled tale of hard won love and understanding between a plain, Jewish golem and passionate Syrian Djinni is surely one that’s worth telling on the big screen.

Is it too obvious to cast Gwendoline Christie as the large, awkward golem, Chava? I think so. So how about the far less obvious Hayley Atwell? Yes, she’s gorgeous, but Hollywood can plainify her, and I think she exemplifies that warm, down-to-earth endurance that is central to Chava’s character.

Chloe Grace Moretz as Emily in Lexicon

Moretz has proved her acting and action chops in such diverse films as Let Me In and Kick Ass. She would be perfect as the vulnerable, manipulative, hyper-intelligent and ass-kicking Emily in last year’s barn-storming techno/psychological thriller, Lexicon by Max Barry.

So those are my picks for female-oriented films I’d love to see. What are yours? The joy of this exercise is that anyone could and should be doing it – the more the merrier. Perhaps eventually Hollywood will sit up and take notice?